The 10 Best Tools to Stay Mentally Sharp at Work

How can you maintain peak concentration during difficult tasks? (Besides just chugging coffee, of course.)

Staying sharp can be tricky. Even when you desperately need to focus, it can be hard to stop a wandering mind. You might get stuck, unable to push past what ought to be a simple problem. Persisting through these moments of frustration can require a lot of willpower.

Below, I’d like to touch on ten tools I use to stay mentally sharp. While doing so, I’ll shine a light on some of the cognitive science that makes them work.

1. Take “Smart” Breaks

There’s nothing wrong with taking a break. Taking your mind off a problem, at least temporarily, can even lead to a breakthrough. When your attention is diffuse, it’s easier to make the longer-range connections you need to solve creative problems.

Checking email or Facebook, however, can make it hard to return to the task at hand. If you need a break, the best strategy is to take “smart” breaks—activities that are unlikely to become an ongoing distraction. Some good ones include:

- Briefly meditating or just sitting with your eyes closed

- Going for a ten-minute walk

- Stretching or doing push-ups

- Getting a glass of water

The idea here is to make the break relaxing, not distracting.

2. Wean Yourself Off Your Phone

What makes a difficult task effortful?

One theory says our perception of effort is actually a calculation of opportunity costs. Your brain has a limited capacity for attention-demanding tasks. Focusing on one thing means ignoring something else. It would make sense for there to be a system that discourages getting stuck on low-value activities.

The problem is what counts as “low value.” Sometimes we really need to do something, but it’s not the kind of activity our brain finds naturally rewarding. We need to study, but our brain finds TikTok videos more fun instead.

One way to make hard work less effortful is to reduce the salience of tempting alternatives. If you never work with your phone accessible, the thought of quickly checking social media isn’t nearly as powerful. Creating working spaces or times where distractions aren’t accessible prevents getting derailed and can make the work less effortful as well.

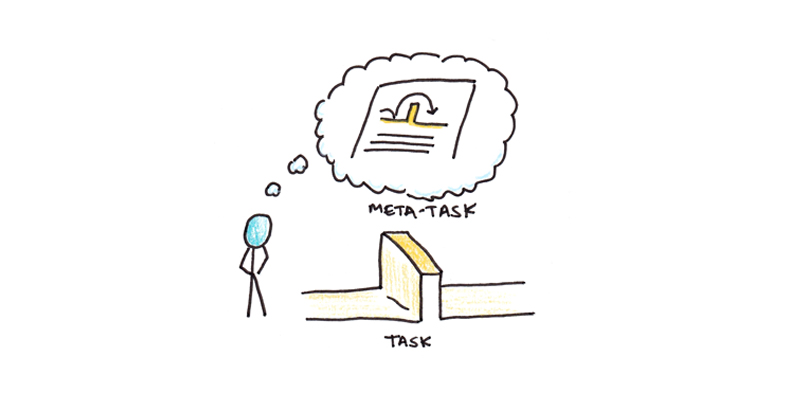

3. Shift to the “Meta” Task

Sometimes you get stuck. How can you get out of it?

One trick I like to use I call switching to the “meta” task. Meta comes from the Greek μετα, meaning “after” or “beyond” and indicates a shift to a more abstract layer of a problem. The idea here is if you get stuck in the task itself, you can shift your attention to figuring out why you’re stuck.

Say you’re writing an essay, and you’ve been staring at a blank page for an hour. Switching to the meta task would mean, instead of writing the essay, write about how you don’t know what to write.

This exercise can help you articulate the difficulty you face and find a solution. You might, for instance, recognize that your problem is that you’re worried you’ll write a bad first draft. But then you realize you can always edit it later, so you commit to writing badly and editing later. Alternatively you might recognize that you’re missing a good opening, so you can start writing the middle sections instead. Either way, you’re now un-stuck.

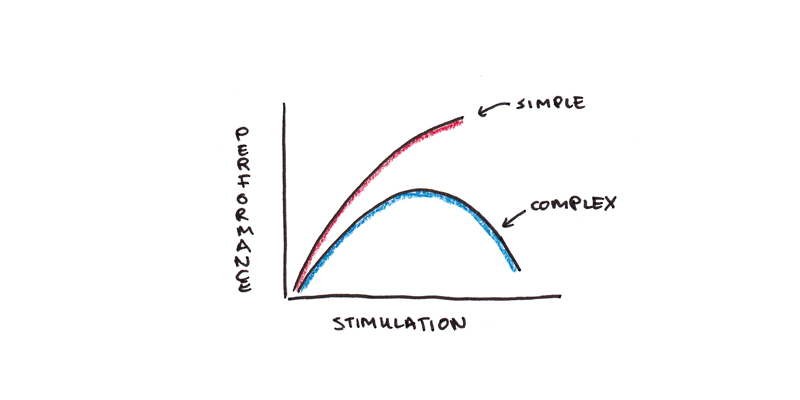

4. Apply the Yerkes-Dodson Law

One of the earliest findings in experimental psychology was the Yerkes-Dodson law, a U-shaped relationship between general arousal and perrformance. Psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson found that performance suffered when subjects were either too alert or relaxed.

Another finding related optimal arousal to task complexity. Simpler tasks benefited from higher degrees of focused alertness, whereas higher arousal hurt performance for more complex tasks.

What does this mean for your work? One implication is that you need to find the right degree of stimulation to keep you focused. If your attention keeps wandering off, you may work better in a noisier coffee shop than in the library. Conversely, if you’ve already had a third cup of coffee, the library may be better.

Another implication is that more complex, creative work benefits more from a relaxed kind of focus. Even if you’re able to work through simple tasks while under a lot of pressure, lowering your anxiety and stress about a task, say through visualization or meditation, helps with high-performance work.

5. Set Specific, Achievable, Short-Term Targets

Edwin Locke pioneered the study of goal-setting. His research found that specific, challenging goals resulted in higher performance. These did better than “do your best” goals or non-specific targets.

Since then, industrial psychology has generally supported the value of goals in increasing performance. However, there are some caveats:

- For complex tasks, a goal-oriented approach may inhibit performance. Maintaining the goal in mind leaves less space in your working memory for exploring the problem. Thus, for novel or frustrating tasks, a playful attitude where you just try things out may be more appropriate.

- Goals only work if they’re accepted. Giving someone a goal they don’t believe is achievable makes it more likely that they will reject the goal, and thus, it will fail to have an effect.

Before any session where you need to focus, clearly spell out what you want to accomplish. Setting a moderately challenging goal you believe you can achieve will help focus your mind in ways that just clocking in cannot.

6. Cultivate an Interruption-Free Environment

How do you stay focused when you constantly get urgent emails from your boss? Your deskmate is loudly typing beside you? Your three-year-old keeps coming to your home office to “ask a quick question”?

The key to improving focus is to negotiate your environment in advance. Most of the time, the people around you would like you to be more productive. The problem is one of communicating what you need and making concessions to keep your relationships smooth.

A boss might be fine with a reply in an hour, provided she knows you haven’t forgotten the new task. Colleagues (and many children) can respect a closed door if they know it means you’re doing deep work. The difficulty is often one of planning the environment ahead of time, not just getting frustrated afterward.

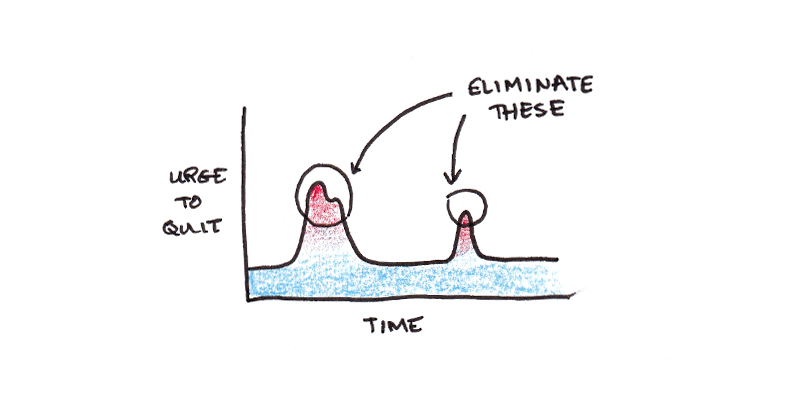

7. Jam Your Quitting Triggers

How do you persist for hours on work that makes you want to quit after only a few minutes? Perhaps it’s working through a difficult assignment, reading a dense manual or finally getting started on a task you’ve been dreading.

One key thing to recognize is that the urge to give up is rarely constant. Even in the most miserable assignment, your actual moment-to-moment mood varies quite a bit. What often happens is that the urge to quit arrives at specific, predictable moments. Identify those moments, and you can use a light touch to defuse them.

Say you need to grind through flashcards to prepare for a test. Every time you get a few wrong in a row, you feel a strong urge to take a break. Instead, set a rule for yourself: I can take a break whenever I get the last one correct. What happens? Now your exit from the task is only after a little positive reinforcement, so it’s harder to simply drop it, and easier to start again later.

Perhaps your problem is with giving up before you begin. Setting a timer for twenty minutes and only letting yourself quit after it dings can keep you in the game long enough to get into a flow. Committing to work for at least twenty minutes is much easier than committing to work for three hours straight, even if it may have a similar effect.

8. Master the Power Nap

Sleep is essential for thinking. With less and less sleep, our mental performance deteriorates. In one study, after losing sleep for multiple nights in a row, subjects thought their fatigue was leveling off, even though their performance kept declining.

While little can replace getting a full night’s sleep, being able to take a nap can help. The key is to avoid getting into the deeper stages of sleep that lead to grogginess later. Roughly twenty minutes is a good length of time for a nap.

As an additional strategy, you can take a coffee nap. Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors. However, it is less effective if those receptors are already activated. A quick nap can remove some of the adenosine and replace it with caffeine to temporarily improve your mental performance.

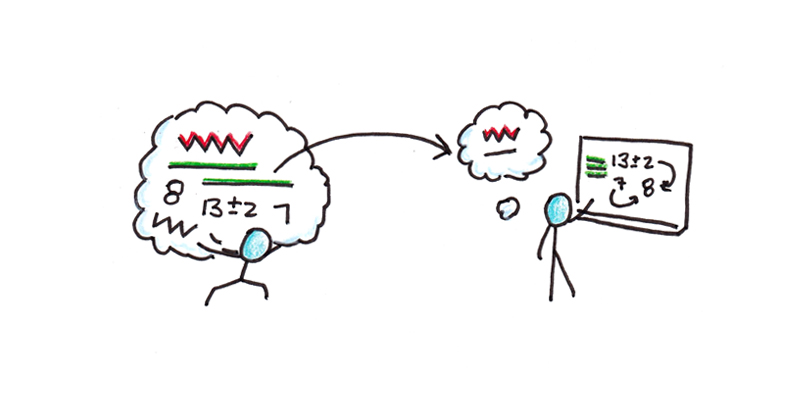

9. Minimize Mental Overhead

Working memory is the psychological concept that corresponds closest to what we think of as mental bandwidth. It’s the things you’re actively thinking about right now. Working memory is in contrast to long-term memory, which is everything you know and remember, whether you’re thinking about it or not.

The critical thing to realize about working memory is that it is limited. George Miller famously pegged the quantity of information as seven, plus or minus two, items. More recent research, however, suggests it may be as low as four items. Compare that to a computer’s RAM, which today can easily store 16,000,000,000 units of information.

One way to cope with limited working memory is to offload what you’re doing onto paper. Writing allows you to externalize your thoughts so you can see new connections. Getting in the habit of regularly writing down your thinking can be a great tool for problem-solving.

10. Don’t Play the Polar Bear Game

Let’s play a game. The rules are simple: don’t think about polar bears. Ready, go!

Did you think about polar bears?

Trying to suppress a thought tends to backfire. This effect is known in psychology as ironic processing, originally studied by Daniel Wegner.

Although we recognize the self-defeating nature of the polar bear game, we often slip into the same pattern when it comes to our focus. We attempt a task, notice our mind is wandering and chastise ourselves, “I need to stop daydreaming and work!” Except, this tends to make focusing even harder.

Mindfuness meditation offers a solution. Meditators have long recognized the futility of trying to suppress an unwanted thought. This can be particularly hard when distracting yourself with a different thought isn’t desired either. The solution is to be gentle with yourself. Let the distraction come and go, without getting ruffled.

Some days you’ll feel sharp—the writing will flow, the code will compile and your problems will seem easy. Other days will feel more like a slog. When the latter come, don’t beat yourself up. Just calm your mind and let yourself gently return to the task.

by Scott Young